Spring 2010: Of Note

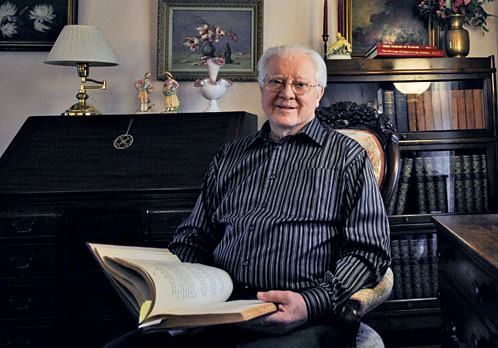

Edgar Francisco III 56G.

Photo by Erik Lesser/Special

To see the slideshow, please enable Javascript and Flash Player.

A Diary’s Secrets

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” —William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

By Allison Adams 00G

Sally Wolff-King 79G 83PhD knew almost the instant she opened the typescript copy of the century-and-a-half-old journal that she was onto a stunning literary discovery.

“It fell open at a place that had a ledger with the amounts of monies paid for individual slaves,” she says. “And it looked just like Go Down, Moses. It was an amazing moment.”

What she read was eerily similar to a passage in “The Bear,” a story in William Faulkner’s 1942 collection of stories, Go Down, Moses, in which the protagonist opens an old leather farm ledger to uncover the truth of his family’s slave-owning history. The diary in Wolff-King’s hands appears to have inspired that passage—and, she would discover, many other stories, characters, and details throughout his body of work.

How Wolff-King, who teaches Southern literature and served as associate dean and assistant vice president, unearthed this wellspring of ideas for the 1949 Nobel laureate in literature is, as she says, “a uniquely Emory story.” It is also the story of one family’s multigenerational struggle to come to terms with its conflicted history of slave ownership.

Wolff-King came to Emory in the 1970s to study with Floyd Watkins, Candler Professor of American Literature. For more than a decade, Watkins had been taking Emory undergraduates on a literary pilgrimage to Oxford, Mississippi, to visit Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s home. Through those visits, Watkins and Wolff-King came to know William Faulkner’s nephew, and in 1996 they published a collection of conversations with him. While continuing to lead the pilgrimages, Wolff-King began work on a second volume of interviews with people who knew Faulkner. Two years ago, she invited Emory alumni to join the trip.

A few miles northeast of Emory in an Atlanta suburb, Edgar Francisco III 56G and his wife, Anne Salyerds Francisco 54G, received that invitation. At his wife’s urging, Francisco wrote to Wolff-King: while he could not join her on the trip, he thought she might like to know that he had known Faulkner.

An economist who earned his doctorate from Yale University and worked in health care policy (including the creation of Medicare and Medicaid), Edgar Francisco grew up in Holly Springs, Mississippi. His father, Edgar Francisco Jr., and Faulkner had grown up together. The two men, Francisco says, shared a bond in their hunting and storytelling. “They would go quail hunting and then come in and have several beers. [Hunting] had been a tradition with those two men from the time they were nine years old.”

Francisco remembers spending many hours as a young boy in the 1930s listening to the two men talk. Mostly Faulkner would listen to his friend Edgar tell family stories. “He was a wonderful storyteller. Faulkner would say, ‘Edgar, tell me that story again.’ And Dad would be glad to tell it again. Faulkner would be taking notes.”

When Wolff-King first interviewed Francisco in March 2008, she was thrilled to find a new source of personal stories about Faulkner, but she had no idea of the treasure he held. Neither, for that matter, did Francisco. Then, in the midst of a conversation about Francisco’s family history, Anne suggested, “Why don’t you show her the diary?”

Francisco hesitated, then he left the room and returned with a library-bound copy of eighteen hundred pages of farm journals kept by his great-great-grandfather, Francis Terry Leak, a wealthy plantation owner, between 1839 and 1862. When Wolff-King saw those stunning ledger entries, she asked Francisco, “ ‘Have you ever read Go Down, Moses?’ But Francisco said, no, he hadn’t read much Faulkner. I said, ‘Well, do you think your father ever read Go Down, Moses?’ ‘I doubt it,’ he said.

“I was struggling to figure out how this document and Go Down, Moses could resemble each other so closely. Finally, I said, ‘Do you think William Faulkner could have ever seen this diary?’ And he said, ‘Oh, yes, he liked to look at it.’ ”

Indeed, writes Wolff-King in an article recently published in the Southern Literary Journal (her book is forthcoming in June from LSU Press), Faulkner not only read the diary but “pored over” it “many times” during the course of about twenty years. Sometimes, Francisco says, he and his father would find Faulkner speaking aloud at the diary as he read: “[He] would be sitting there, cursing away and taking notes.”

It was, says Wolff-King, “as if he were in conversation with the diarist,” a slave-owning Confederate supporter. “I suspect that Faulkner was arguing with history.”

Wolff-King guarded her secret for two years, until she had completed some careful analysis and research. She borrowed the typescript copy (Francisco’s family had donated the original books, which scholars have mined for insights into antebellum culture, to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill library in 1946) to follow a trail of evidence from the diary into Faulkner’s fiction. She traced it across a broad range of works, in details such as the construction of a plantation house (Absalom, Absalom!) and the ticking of a watch (The Sound and the Fury). Most poignantly, however, the names and particular qualities of slaves documented in the diary seem to have ended up in some of the more sympathetic characters in the novels. “Candis,” a slave on the Leak plantation, perhaps became “Candace,” a heroine in The Sound and the Fury.

“To me it seems that he was sympathetic with the slaves and their plight,” Wolff-King says, “and by resurrecting their names and recounting some of their stories, he memorialized them.”

Francisco kept silent for all those years about his family’s relationship with Faulkner because revealing it also makes public his own argument with history. The efforts of one great-great-grandfather, John Ramsey McCarroll, to end slavery before the war enraged his other great-great-grandfather, the loyal Confederate, Francis Terry Leak. After the Civil War, the two families were bound by marriage yet remained in conflict over property disputes. The diary came to represent that painful past.

For Francisco, who volunteered as an Emory student with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and helped plan the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, his family’s slave ownership was also difficult to face. He senses that Faulkner’s writings resonate with this conflict. “If I started trying to read one of the books I got very apprehensive that I was going to find something out that I wouldn’t like to know,” he says. “I didn’t want to recall it, whatever was there.”

Francisco adds that as a child, “When I found out that the man Faulkner was furious with was my great-great-grandfather, I reached the conclusion that he was angry with me. And that he wouldn’t want to talk to me any more, that I had lost my friend. I adored him. I knew he was important.”