Autumn 2010

The Carter Center

Breaking a Vicious Cycle

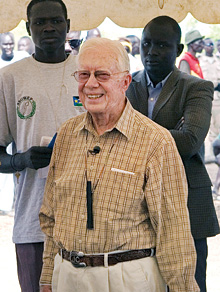

Jimmy Carter is planning a send-off for the last Guinea worm on earth

Related Story

“Lost and Found” David Thon 08MPH fled his rural village in search of a safe haven, eventually emigrating to the United States in 2001. Last year, on behalf of The Carter Center, he returned home to help eradicate an ancient scourge, ‘waging peace’ one patient at a time.

By Patrick Adams 08MPH

Founded in 1982 by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn Carter, The Carter Center, in partnership with Emory, has worked to advance human rights and alleviate human suffering in more than seventy countries. One of the center’s core activities, the Guinea Worm Eradication Program, is nearing the finish line, with only four countries still reporting cases. President Carter spoke with Emory Magazine about the program’s impressive achievements and the lessons learned along the way.

The Guinea Worm Eradication Program has made tremendous progress during the past twenty-five years—particularly in Nigeria, once home to the highest number of cases, and in Sudan, which has reduced disease incidence by 99.7 percent since activities were expanded there in 1995. As you reflect on that progress, what have been the program’s biggest challenges?

The first one was just to address this issue at all because no one else wanted to touch it. The second thing is that it’s a disease that quite often is not known in the urban areas, where the political focus remains and the power exists. For instance, when I went to Pakistan first, neither the president of the country nor his minister of health even knew about Guinea worm. Fortunately, the prime minister of Pakistan at that time had come from a village that had Guinea worm, so that made it possible for Pakistan to be the first nation to eliminate Guinea worm completely.

Third, it depends on the complete ending of the cycle [of transmission] for an entire twelve months. When somebody is infected with Guinea worm, there’s no way for them or any others to know they’re infected until the worm becomes mature, and that can take almost a year.

The fourth problem is that quite often, the people who use the water hole are migrants; they don’t live there, they just travel from one place to the other during the farming season or take care of their cattle or sheep or goats. And the fifth problem is that any outbreak of violence, as [took place] in Mali and parts of northeast Ghana and certainly in southern Sudan, makes it impossible for our workers to go in there to take care of the problems.

Critics of so-called “vertical programs” that target a single disease point to their inability to address the context of poverty or a lack of access to primary care. But the Guinea Worm Eradication Program has helped move countries closer to achieving a number of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals—including universal primary education, gender equality, and improved access to safe drinking water. What we’ve done is use Guinea worm as a foundation to take on other things, including economic development, other health issues, and sometimes political problems that exist in the same villages. Guinea worm has served as an entrée for us to go in, and once the people see that because of our help and their own work they can actually make an accomplishment, then they get interested in working on these other things.

Last February, you visited a Guinea worm-endemic village in southern Sudan. Can you talk about that experience?

Well, at that time they were treating people who still had Guinea worm emerging from their bodies, and I think that particular village might be the last place that we’ll see Guinea worm on earth.

I wanted to let them know that not only a former president but that the world is interested in what occurs in their particular village and that they might very well be the ones who will be honored with recognition when and if their last case of Guinea worm is treated.

At the very start of our program, I went to all the endemic countries, met with the president or the king or the prime minister, and formed a contract with them about what The Carter Center was going to do and what we expected them to do, and it was because of those early contracts that we’ve had such good cooperation.

Does the Guinea Worm Eradication Program have lessons for other eradication efforts?

It has not only lessons but also encouragement for other eradication efforts. I think in addition to the officials in Washington and Geneva, it shows the individual ministers of health in all of the countries involved, as well as the governors and local village leaders, that we can actually do something to correct a serious problem by our own acquisition of knowledge and our own adherence to the rules. Guinea worm is an ancient disease that has afflicted people for ages. And I would say the most important thing is the beneficial effect for human beings who will never have to suffer from it again.