Autumn 2010

“We are exploring how the place where people live—meaning the physical and social environment—impacts their lives over and beyond individual behaviors,” says Professor of Public Health Claire Sterk.

Positive Signs

Even as the HIV/AIDS pandemic continues its stealthy global advance, Emory scientists are striking blows against the virus from all directions

Audio Slideshow

“Hope for an AIDS Vaccine,” Autumn 2010

Video

“HIV/AIDS Research at Emory University, ” September 13, 2010

By Mary J. Loftus

Discovering new antiretrovirals. Analyzing immune response. Targeting simian versions of the virus. Developing vaccines. Enlisting volunteers for clinical trials. Examining transmission in Zambia. Caring for veterans with the virus. Surveying women to learn how gender and stigma affect vulnerability to sexually transmitted diseases. Hiring a dean who led the Centers for Disease Control’s first task force on the virus—even before it was called Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

Emory can claim its share of victories in the world’s war against AIDS, which has taken 25 million lives since 1981. Likely leaping from monkey to man, then traveling from human to human through our most intimate connections—in blood, semen, breast milk—the retrovirus has been in an exponential race for its own survival, outmaneuvering our attempts to contain it and teaming up with a host of opportunistic infections eager to ravage an already compromised immune system. The AIDS pandemic has devastated countries and communities, taken the poorest of the world and made them poorer, and created millions of individual stories of illness and loss.

The statistics boggle the mind: More than 33 million people worldwide are living with the virus, as many women as men. Despite effective antiretroviral treatment, more than two million die from AIDS each year—three hundred thousand of them children. AIDS has created 14 million orphans in Africa. Here in the United States, nearly six hundred thousand people have died from AIDS, and more than one million are living with the virus (with one in five of these unaware of their infection). In the greater-Atlanta area, more than twenty-six thousand people have been diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. And we have not yet seen the dip in the bell curve; about 2.7 million more people will develop AIDS this year alone.

To paraphrase the late Jonathan Mann, former head of the World Health Organization’s global AIDS program: This plague has given our generation a historic responsibility that demands a global response.

Dennis Liotta and Raymond Schinazi

Jon Rou

Miracle by Mouth

More than 90 percent of people in the U.S., and many around the world, who are on medication for HIV/AIDS take antiretroviral drugs developed at Emory. In the early 1990s, Professor of Pediatrics Raymond Schinazi, Professor of Chemistry Dennis Liotta, and researcher Woo-Baeg Choi codeveloped the molecules 3TC and FTC, which help to prevent or delay HIV from replicating and infecting other cells. “Everyone was intrigued, but skeptical about our work—no one realized the importance of what we had found,” Schinazi says. The scientists pushed for grants that would allow them to continue their research. Soon, FTC, or Emtriva (the “Em” stands for Emory) and 3TC (Epivir, which also treats the Hep B virus) were recommended by the World Health Organization as part of a first-line drug treatment regimen. Ultimately the discovery would lead to a $540 million deal for the researchers and the University—one of the largest royalty sales in the history of higher education. Atripla, a combination of Emtriva and two other previously approved drugs, now enables many patients to take just one pill a day, down from ten to fifteen pills a decade ago. “It’s like having an H-bomb for HIV. You blow it to smithereens with one simple pill—the virus doesn’t know how to escape,” Schinazi says. Schinazi and Liotta continue to work at Emory in AIDS research and have founded several companies and research institutes in Atlanta and abroad. Liotta started the Republic of South Africa Drug Discovery Training Program to give African scientists the tools to combat infectious diseases in their own countries. “The transfer of money and technology isn’t enough,” Liotta says. “Expertise in the discovery and development of new medicines is the intrinsic requirement.”

Research Synergy

The Emory Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) is one of twenty such National Institutes of Health (NIH) programs throughout the United States. Emory’s CFAR encompasses 260 University-affiliated researchers, and its programs emphasize the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration (especially between basic scientists and clinical investigators), translational research from lab to clinic, inclusion of minorities, and strategies for prevention and behavioral change. Annually, Emory receives more than $50 million in HIV/AIDS-related research funding.

Forefront and center

The Emory Vaccine Center

Jack Kearse

One of the largest academic vaccine centers in the world, the Emory Vaccine Center at Yerkes is housed in a three-story, seventy-five-thousand-square-foot building that includes the Yerkes Division of Microbiology and Immunology. In the center’s twenty-six research laboratories, scientists are working to develop vaccines for HIV, malaria, and other emerging infectious diseases. The NIH recently awarded a five-year, $15.5 million grant to researchers at the center to study human immune responses to vaccinations, which will guide the design of vaccines. The center is directed by Professor of Microbiology and Immunology Rafi Ahmed, a Georgia Research Alliance Scholar, who believes that understanding the intricacies of long-term immune memory is key. “The world still desperately needs effective AIDS vaccines, and the Emory Vaccine Center is at the forefront of development,” Ahmed says.

Emory doctors like Jeffrey Lennox, above, care for the largest university cohort of HIV/AIDS patients in the country.

Kay Hinton

Hands On

Advancing technologies and the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy are allowing people with HIV to live longer, richer lives. “The average lifespan, once someone is diagnosed and on treatment, is about twenty years, with recent estimates extending to thirty years,” says Vice Chair of Medicine for Grady Affairs Jeffrey Lennox. “For someone diagnosed at age thirty, that means they will live until sixty with HIV.” Emory doctors care for more than seven thousand HIV/AIDS patients—the largest university cohort in the country—through three Emory-related sites. Grady Health System’s Ponce de Leon Center, directed and staffed by Emory infectious disease specialists, serves about five thousand patients, and another several thousand people with HIV or AIDS are treated at Emory University Hospital Midtown and the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, a primary teaching hospital of Emory’s medical school. Each site is also conducting research and clinical trials related to HIV/AIDS. Lennox is now conducting a National Institutes of Health study of 1,800 patients, comparing several different regimens recommended as first-line treatments to determine their relative advantages. “Emory is poised to do some really important work, but it’s more than any one university can do,” Lennox says. “We’ve been trying to conquer HIV for thirty years now, and we still don’t have a complete understanding of why people’s immune systems fail. But we are getting much, much closer.”

Early Promise

Harriet Robinson

Jack Kearse

One of the leading AIDS vaccine candidates was discovered in microbiologist Harriet Robinson’s lab at the Emory Vaccine Center at Yerkes National Primate Research Center and developed at the biotech startup GeoVax. “The vaccine is proving safe and inducing good immune responses in humans,” says Robinson, now chief scientific officer at GeoVax Labs. The vaccine uses two doses of DNA that encode a harmless mimic of HIV (close enough that the immune system could “recognize” the virus if infected in the future) as well as two doses of a recombinant modified vaccinia virus. It has been highly effective in rhesus macaque monkeys and is currently in Phase II clinical trials, with human trials being conducted by the NIH-sponsored HIV Vaccine Trials Network. Although Robinson left Emory in 2008 to develop the possible HIV vaccine with GeoVax, she continues her collaboration with Yerkes Research Associate Professor Rama Amara, using nonhuman primate models to study the ability of the vaccine to serve as a therapy for already established infections and work on new vaccines for both prevention and therapy. “The next-generation preventative vaccines are showing very impressive results,” Amara says.

Great Minds, Think Vaccine

This fall, about a thousand scientists dedicated to finding an HIV/AIDS vaccine gathered in Atlanta for the tenth-annual AIDS Vaccine 2010 conference, cosponsored by Emory’s Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) and the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise. This annual conference brings together everyone from immunologists to policymakers. “To move toward an effective AIDS vaccine . . . what we have to do is tap innovative young talent and bring young investigators into the field,” says conference chair Eric Hunter, a pathologist and codirector of Emory CFAR. Rollins School of Public Health Dean James Curran and chair of the Hubert Department of Global Health Carlos del Rio, also CFAR codirectors, were cochairs, along with AIDS vaccine researcher Harriet Robinson of GeoVax Labs.

Indian Frontier

A recent partnership between the Emory Vaccine Center and the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB) in New Delhi, India, will address the development of a protective AIDS vaccine that targets the strain of HIV most prevalent in India and sub-Saharan Africa, known as subtype C. This will mark the first time such a vaccine has been researched in India specifically for the people of India. These efforts are desperately needed, as approximately 2.5 million people in India are currently living with HIV, a number that puts those not infected at high risk of contracting the virus.

Curran in Science magazine, 1983

Courtesy WHSC

Think back to 1981

Before AIDS became a pandemic, it started as a mysterious syndrome—young gay men in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York City were experiencing fatal pneumonias, rare cancers, and other puzzling ailments. Rollins Dean Jim Curran was chief of the research branch of the division of Sexually Transmitted Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta at the time, and was named head of the task force assigned to investigate this new disease. Because the earliest cases appeared in gay men, as well as men and women who injected drugs, the CDC determined that it was most likely an infectious agent, probably a virus, that could be transmitted through blood and sexual contact. Curran remembers a Frontline interview when the first AIDS cases were reported in hemophiliacs, who require frequent blood products, and public panic grew: “Great concerns about the blood supply, great concerns about sexual transmission, great concerns about transmission through casual contact followed.” In 1982, the CDC began using the acronym AIDS to refer to the epidemic. The first International AIDS Conference was held in Atlanta in early 1985. Curran attained the rank of assistant surgeon general before leaving the CDC in 1995 to become a professor and dean of the Rollins School of Public Health. He’s also a principal investigator and codirector of Emory CFAR, continuing to research the insidious virus that he encountered some thirty years ago. “Three things—denial, discrimination, and scarcity—are the enemies of AIDS prevention, and they’re always going to be there,” Curran says. “They’re just there over and over and over.”

Courtesy WHSC

AIDS in Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest prevalence of HIV infection worldwide, mostly due to heterosexual transmission. Professor of Pathology and Global Health Susan Allen and Professor of Pathology Eric Hunter, spouses as well as colleagues, study HIV transmission between married or cohabiting couples in Rwanda and Zambia. “The majority of new HIV infections are acquired from a spouse, and couples are the largest HIV risk group in Africa,” Allen says. Joint HIV testing, she says, reduces new infections in couples by half to two-thirds. Hunter’s laboratory investigates the molecular mechanisms underlying HIV transmission among these couples, with an aim toward developing novel vaccine approaches.

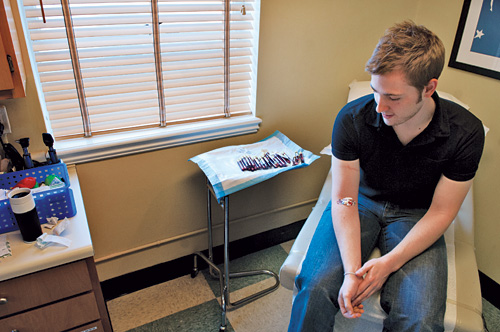

HIV-negative volunteers like Robert Parker, above, take part in AIDS vaccine trials at Emory’s Hope Clinic. “It’s a pretty big decision to make,” says Parker, whose partner is also a volunteer. “But if I’m not willing to do it, who will be?” For more on Parker’s story, go to www.emory.edu/magazine.

Kay Hinton

Testing, Testing, 1-2-3, Hoping

As a child growing up in a conservative Massachusetts town, Robert Parker got the message that AIDS was a righteous punishment delivered by God to sinners. Now twenty-three, Parker decided to debunk that stigma by becoming one of hundreds of community members who are taking part in AIDS vaccine trials at Emory’s Hope Clinic in Decatur. “A true cure will be found only if people choose to participate,” Parker says. The Hope Clinic is the clinical arm of the Emory Vaccine Center, recruiting HIV-negative volunteers to test promising prevention vaccines in NIH-sponsored clinical trials. “The vaccine trials we are doing are absolutely critical,” says medical director Mark Mulligan. “We are conducting the only HIV vaccine efficacy trial in the world that is currently enrolling participants. Ultimately, to extinguish this pandemic, we need a prevention vaccine.”

Race, drugs, and sex in the city

Carlos del Rio

Bryan Meltz

City dwellers living below the poverty line in America—a group that includes a disproportionate number of minorities—have much higher rates of HIV infection. Chair of Global Health at Rollins and codirector for Clinical Science and International Research in Emory’s CFAR, Carlos del Rio has long been an advocate for people who are HIV-positive, lobbying for them to have ready access to care in comprehensive clinical environments, which increases the likelihood that even the uninsured will take antiretroviral medications regularly. Del Rio, executive director of the National AIDS Council of Mexico from 1992 to 1996 and former chief of Emory Medical Service at Grady, has conducted research on access to HIV testing and care for underserved populations in Atlanta since 1998. One of his recent studies found that 60 percent of Atlanta’s HIV cases were in an area of the city with a large number of people living in poverty, black residents, men who have sex with men, and drug users.

Cycling for a cause: The ride’s unrestricted funds fill gaps that can’t be met by grant dollars alone.

Courtesy Tamzen Pickard

Pedal Power

For the eighth year in a row, bicyclists in the Action Cycling Atlanta’s 200-Mile Ride pedaled two hundred miles in two days to raise $188,660 for AIDS vaccine research at the Emory Vaccine Center. The AIDS Vaccine 200 in May attracted more than 130 cyclists. The annual ride now has raised more than $680,000 for AIDS vaccine research. This year’s riders traveled a scenic route from Emory to Eatonton, Georgia, in the Oconee National Forest and back to Emory along with a volunteer crew. Because of sponsorships, Action Cycling is able to donate 100 percent of proceeds.

Risky Business

Gina Wingood and Ralph DiClemente

Jack Kearse

Agnes Moore Professor Gina Wingood, codirector of CFAR’s Prevention Science core, surveyed a thousand black women and five hundred white women to find out how they confront issues that affect their sexual health—and, ultimately, their vulnerability to HIV/AIDS—as principal investigator of the five-year study, Social Health of African American and White Women’s Lives (SHAWL). “It’s likely that HIV transmission depends in important ways on gender, stigma, discrimination, or socioeconomic status,” says Wingood, shown seated at left. This is just one study in a vast body of applied research and HIV prevention programs produced by CFAR scientists—including Wingood’s spouse, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Public Health Ralph DiClemente, above right, who investigates risk factors in adolescents such as exposure to sexual content on the Internet and in rap videos. Research Professor Kirk Elifson and Charles Howard Candler Professor of Public Health Claire Sterk, a founding member of CFAR, also have worked for two decades on community-based research involving HIV-vulnerable populations, such as sex workers and homeless persons, who often don’t access mainstream services.

Aging patients, new research

The majority of the HIV-infected population in the U.S. will likely be older than fifty by 2015. Researchers at Emory’s School of Medicine have shown in an animal model that the presence of HIV proteins, even without a replicating virus, leads to alterations in cells that break down bone. Assistant Professor of Endocrinology M. Neale Weitzmann says this study can “help doctors decide the best way to stave off osteoporosis and bone fractures, which are becoming increasingly common in individuals living with HIV.”

Nonhuman Primates

Jack Kearse

Studies performed at Emory’s Yerkes National Primate Research Center have been critical for testing the DNA/MVA vaccine, illustrating the value of the simian immunodeficiency (SIV) virus model in rhesus macaques. In addition, work by investigators such as leading HIV scientist Guido Silvestri, chief of the Division of Microbiology and Immunology at Yerkes, studying sooty mangabeys could reveal how some primates survive infection by SIV without having their immune systems crippled, as well as how HIV may have migrated from nonhuman primates to humans.