Spring 2009: Prelude

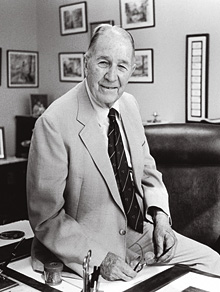

Former Board of Trustees Chair Henry Bowden 32C 34L 59H led a legal challenge that helped Emory desegregate.

Billy Howard

Life After Brown

By Paige P. Parvin 96G

In 1960, my predecessor several times removed, Randy Fort, published a special issue of the Emory Alumnus with the theme “Crisis in the Schools.” At the time, Emory was wrestling with the deeply difficult question of desegregation in the wake of the 1954 Brown decision. The president, Walter Martin, was walking a fine line, trying to keep the peace among groups of alumni and trustees who were divided on the issue—with many opposed to desegregation—and faculty and students who were largely supportive of change. Eventually, Henry Bowden, chair of the Board of Trustees, would lead a legal challenge that enabled Emory to desegregate without losing its tax-exempt status, eliminating a major obstacle and paving the way for black students.

In the Alumnus, Fort did not argue passionately for desegregation, but he did praise Emory as a place where it could be safely and candidly discussed. He also highlighted the very real problems the issue created for the University: as Georgia legislators vowed to close public schools rather than desegregate, the entire system threatened to crumble, taking Atlanta’s booming business growth and rising stature down with it.

“Emory has had turndown after turndown from able young teachers it has wanted to employ from colleges in other states,” Fort wrote. “They simply would not bring their children into a climate where the future of public education is uncertain. Nor will many professors now at Emory stay any longer if the situation grows much worse.”

Emory has an incredibly rich past—and present—when it comes to matters of race, and in these pages we are able to offer only a smattering of its stories. Still, I am honored to follow in Fort’s footsteps, nearly a half century later, with this issue of Emory Magazine devoted to the legacy of civil rights.

Many of those we spoke with during past weeks could not help but reference the election of President Barack Obama as a defining moment in American history. But nearly all, I noticed, were quick to add that Obama’s presidency does not mean the march toward full racial equality can now come to a halt. As Professor Rudolph Byrd, founding director of the James Weldon Johnson Institute, put it, “The election of one individual to an office does not mean the end of centuries of white supremacy. It represents enormous progress, but the struggle continues.”

In that spirit, much of this issue is focused not on past struggles, but on current efforts and future promise. The Johnson Institute, dedicated to civil rights scholarship, held its formal launch in April. Brad Braxton 99PhD, senior minister for New York City’s renowned Riverside Church, has only just begun his tenure as the sixth leader of this famously influential congregation. Emory’s Transforming Community Project, with its sweeping five-year scope, continues to weave colorful new patches into the fabric of the University’s racial culture. Atlanta’s Center for Civil and Human Rights, expected to invigorate the city’s tourism and culture scene and foster ongoing civil rights study, will break ground this winter. And the tale of the ill-fated Atlanta Times, written by Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Hank Klibanoff, is a good reminder that although its channels have changed, the media continues to shape public opinion on issues of race and difference, with last year’s election serving as a case in point.

The demise of the Atlanta Times, fittingly, coincided with the end of Atlanta school segregation. As I read about the struggle that nearly crippled Emory’s growth and fund-raising efforts, the southern educational system, and the city’s progress, I couldn’t help but think of my own public school experience. Raised in a largely white, rural Tennessee county, I didn’t sit in a classroom with African American students until I went away to boarding school as a high school junior.

My son, by contrast, is a product of Atlanta Public Schools, and has shared his experience with black students since pre-kindergarten. His friends are a diverse set that reflect his diverse surroundings. Each year, he has listened to the speeches of Martin Luther King Jr. and studied many other civil rights legends and events during the celebration of Black History Month.

Maybe that explains why, when he saw former President George W. Bush on television for the first time, he exclaimed, “That’s George Bush? I thought he was brown!”

Now we can look to the nation’s first “brown” president and, regardless of our politics, marvel at how far the march has brought us.