Spring 2009: Features

Calinda Lee and Rudolph Byrd guide the Johnson Institute’s mission to link community action with research and teaching.

Kay Hinton

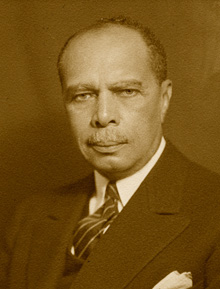

James Weldon Johnson

Courtesy MARBL

Living Legends

The James Weldon Johnson Institute breathes new life into modern civil rights scholarship

By Paige P. Parvin 96G

On a mild spring afternoon, in a ground-floor classroom of Emory’s Anthropology Building, Rosa Parks and Ella Baker are having a serious philosophical conversation.

Soon they are joined by another linchpin of the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. He swaggers into the room, sees the two women, and exclaims dramatically, “I had a dream. And both of y’all were in it!”

The class dissolves into laughter, the role-play threatening to unravel as the starring students fight to keep their faces straight. Professor Robbie Lieberman gently guides them back on track.

This course on the black freedom movement is made up of six students from Emory and seven from Spelman College, a historically black women’s college in Atlanta. The two groups have mixed quickly, according to Lieberman, with class meetings marked by lively and sometimes passionate exchange.

“There is a popular view of the movement, and a lot of this course is about challenging that view, going deeper to gain an understanding of what was really going on,” Lieberman says.

Their joint scholarly exploration of the modern civil rights movement is at the heart of the vision for Emory’s James Weldon Johnson Institute, established in 2007 and formally launched this March. Lieberman, a professor of history at Southern Illinois University, is among the institute’s first four visiting scholars. In addition to teaching, she is conducting research on the uneasy relationship between the peace movement and the African American freedom movement from the end of World War II to the early 1960s, before Vietnam became a major issue.

Supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Visiting Scholars Program is the core initiative of the Johnson Institute, according to founder and director Rudolph P. Byrd, Goodrich C. White Professor of American Studies. With the goal of fostering new scholarship and research on the modern civil rights movement from 1905 to the present, the program is the only residential opportunity of its kind in the nation, Byrd says. Visiting scholars hold joint appointments in the Johnson Institute, the School of Law, and one of five sponsoring academic departments.

Byrd has been the force behind the planning and creation of the Johnson Institute for more than a decade, almost since he joined the Emory faculty in 1991. Prior to that, he taught English and African American studies at Carleton College and the University of Delaware. Byrd’s eight books include The Essential Writings of James Weldon Johnson, coedited with Charles Johnson and published last year.

“For years, I’ve been interested in the modern civil rights movement, and I come to that from the area of literary studies,” he says. “I have always been a great admirer of James Weldon Johnson as the first executive secretary of the NAACP and as a major canonical literary figure. Johnson, it seemed, was the ideal figure to honor through the creation of an institute that would support new research and scholarship.”

Born in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1871, Johnson arguably accomplished enough for several lifetimes, leaving a legacy in the areas of civil rights, literature, law, music, and political diplomacy. He attended Atlanta University and became the first African American to pass the bar in Florida. He wrote and edited a number of books, including the first anthology of African American poetry in English; as a musician, Johnson and his brother coedited The Book of Negro Spirituals and composed the landmark civil rights anthem “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Fluent in French and Spanish, Johnson also was the first African American to serve as a U.S. consul to Venezuela and Nicaragua. Later, as executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Johnson organized the historic Silent March of 1917 in New York and led a national campaign against lynching, nearly securing federal legislation against it. After retiring as head of the NAACP in 1930, Johnson taught English and creative writing at Fisk University and New York University, becoming the university’s first black faculty member.

Although the bulk of Johnson’s archive is held at Yale, Byrd, along with Linda Matthews, then head of Special Collections in Emory’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL), learned in the 1990s of some available historic materials. Eventually Emory acquired a number of Johnson’s documents and artifacts, including correspondence, literary manuscripts by Johnson and others, sheet music, legal documents, Johnson’s own copies of his books, and original photographs that include figures like Carl Van Vechten and W. E. B. Du Bois. Emory also has a highboy dresser that belonged to Johnson, as well as a typewriter (above), tea service, briefcase, and a well-traveled steamer trunk bearing his name.

“It’s great to have these kinds of artifacts,” Byrd says. “It makes the man come alive in very interesting ways. They also were the catalyst for the acquisition of other civil rights materials and strengthened the argument to establish an institute in Johnson’s name.”

The Johnson Institute is supported by a wide network of partners and sponsorships, woven in large part by Calinda Lee 02PhD, assistant director for research and development. Lee was teaching U.S. history at Loyola University when four different friends sent her the job description for the position.

“I had always been interested in the links between scholarship and activism, so the mission of this institute was really appealing to me,” Lee says. “As nonprofits struggle financially, these kinds of institutes are becoming the home of important social justice work. To link community service with scholarship in a meaningful way is really an increasing imperative of universities.”

The Johnson Institute also is home to the Alice Walker Literary Society, a collaboration with the Women’s Research and Resource Center of Spelman College, founded in 1997 and cochaired by Byrd. The Walker archive became part of the African American Collection of MARBL in 2007 and was opened to the public in April of this year.

Resources in MARBL, including the Walker archive, papers of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and many others, are the basis for another Johnson Institute program, funded by the United Negro College Fund (UNCF) and the Mellon Foundation. The UNCF Faculty Residency Program supports faculty from UNCF member institutions who are engaged in research at Emory.

As the African American Collection in MARBL grows richer and more expansive, it draws an ever-widening stream of scholars, researchers, and activists to Atlanta and to Emory, according to curator Randall K. Burkett.

“Some people have deep memories of Emory as a certain type of Southern institution,” Burkett says. “But we now have a national reputation as a place that respects these materials and makes them available. We are attracting different faculty and graduate students because people can do their research here.

“That’s my dream, that people will see Emory as interested in the entirety of American history and culture.”

At the launch of the Johnson Institute, held in Cannon Chapel, Byrd spoke of the election of President Barack Obama as “indisputable proof” of the progress made toward racial equality. But, he cautioned, this historic event represents but a rung in a ladder whose highest point is not yet visible.

“We do not live in a postracial era, a postgender era, a post–civil rights era,” Byrd said. “We do not yet live in an era in which difference is immaterial. As members of a university community and citizens committed to the public good, we aim always for light and truth. We are heartened, even emboldened by our progress, but in the words of the slave poet, ‘We am climbin’ Jacob’s ladder.’ I am, we are, climbing Jacob’s ladder. This is the legacy bequeathed to us by Johnson and so many others. This is the legacy we carry within us as we leave this place.”