Summer 2008

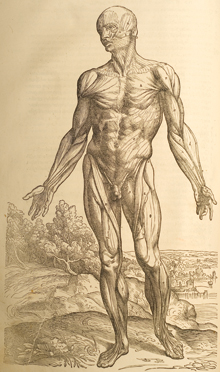

This woodcut illustration is one of the “muscleman” series by Jan van Calcar, which shows the musculature of male bodies “in nature.” The rare volume, now valued at more than $100,000, is located in Emory’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.

Images from the First Edition of physician Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica (1543, Variant A), owned by the Woodruff Health Sciences Center Library, Emory University.

Body of Knowledge

Alumni make the ultimate donation—themselves—to the School of Medicine’s Body Donor Program

Related article

Giving Thanks Students hold service for body donors

By Mary L. Loftus

Lena Ruth McCullough, a 1942 graduate of Emory’s nursing college, appreciated life’s simple pleasures—wildflowers blooming alongside the road, a cardinal perched on a tree branch, the white vapor trail of a jet across a bright blue sky. A World War II Navy veteran and retired nurse, McCullough was neat and orderly, making her beds at home with hospital corners.

But she was also playful, funny, and inquisitive, engaging everyone she met in conversation and taking her grandchildren on trips to goat farms, peach orchards, and the Issaqueena Dam near her home in Clemson, South Carolina.

She enjoyed religious readings, poetry—especially Emily Dickinson—and romantic movies. She liked both Mitt Romney and Barack Obama, but not Hillary Clinton or John McCain. An active member of Clemson Presbyterian Church, she attended Wednesday morning bible study regularly.

When she died on Sunday, May 4, at age eighty-six, with family and friends gathered around her at the hospital, she was picked up by Duckett-Robinson Funeral Home in a hearse and traveled on a flag-draped stretcher the hundred-plus miles to Emory School of Medicine.

McCullough was one of nearly eleven thousand people who have registered to donate their bodies to the Emory medical school’s body donor program when they die—some of whom, like McCullough, are Emory alumni.

Lena Ruth McCullough 42N

Courtesy her family

William Whitaker Jr. 39C 42M

Courtesy Piedmont Hospital Archives

“She made everyone aware that this was her wish,” says her granddaughter, Marie Nebesky, a high school teacher in Clemson. “She felt pride and honor in the possibility that she might be able to make such a generous donation. I think she knew that she would help others to learn and research and discover. She, of course, felt a special connection to Emory and wanted her body to go there first if possible. She carried a card with a telephone number in her wallet, and we informed the hospital staff of her wishes.”

Licensed funeral director and embalmer Jim Cooper, of Emory’s Body Donor Program, spoke with McCullough on the phone several times after she decided to join the registry in 1996. “She was certain that she wanted to come to Emory,” he says.

Donors must personally sign the form, he says. The program does not accept next-of-kin signatures or donations in wills. The decision must be made at least ninety days before the donor dies.

Cooper started working in a mortuary at the age of fourteen, driving its brand-new ambulance with an unrestricted driver’s license, and has been in the business for fifty-one of his sixty-five years. “I was impressed by what morticians did. They were like the Egyptians, preparing the bodies, conducting rituals for the dead,” he said. He served for several years in the army as a postmortuary officer during the Vietnam era.

He’s heard all the stereotypes about undertakers—pale, morbid, skinny, clad in black suits—but he’s more jovial than morose. In fact, Cooper is the one who talks with the donors and their families, making sure everyone is informed and confident in the knowledge that they will be treated with respect and courtesy.

“We have a lot of donors on the preregistry, and many are doctors and nurses. They know we treat them right,” says Cooper, who has been on the Body Donor Program’s preregistry himself since 1989.

Atlanta physician William Whitaker Jr. 39C 42M, who died on April 6 at age ninety of heart disease, is a case in point. After graduating from Emory medical school, he went on to serve as a captain in the U.S. Army Air Corps in World War II. After the war he returned to Atlanta and completed his residency in general surgery at Grady Memorial Hospital, where he was chief resident.

Whitaker served on the staff of several hospitals, including Crawford Long, St. Joseph’s, and Hughes Spalding, making rounds during rush-hour traffic. He continued to make house calls long after they were out of fashion. A deeply religious man, he was a member of Peachtree Road United Methodist Church and always prayed before operating on patients.

Whitaker started a surgical residency program in conjunction with Emory at Piedmont Hospital, where he was chief of inpatient surgery. He practiced at Piedmont from the early 1970s until he retired in 1996 at the age of seventy-eight, largely due to failing eyesight. He enjoyed golfing and salmon fishing in Alaska.

A lifelong financial donor to Emory and a member of the 1915 Club, Whitaker wanted to be sure that, when he died, his body would be donated to Emory’s School of Medicine.

“My father really felt strongly about medical education,” says his eldest son, William Whitaker III 68M, a physician at DeKalb Medical Center in diagnostic radiology who also graduated from Emory medical school, as did one of his three brothers, Julian Whitaker 70M. “I would sign the registry myself, but my wife has other ideas.”

The average age of donor death is eighty-eight, says Cooper, and the body donor program receives between 125 and 150 bodies per year.

Some families are reticent about their relatives’ decision to donate their bodies for scientific research or to a medical school. Others are angry when a preregistered donor is not accepted by the program for logistical or medical reasons. “You can never predict the issue that’s bothering them. Some are grieving and just don’t want to let go,” Cooper says. “But we are here to help these families.”

As Cooper, who has been with Emory’s Body Donor Program for nearly two decades, has taken over more of the administrative duties and family and donor relations, he has turned most of the embalming over to Susan Brooks, also a licensed funeral director and embalmer, who has been with the program since 2002.

“Our embalming is of a higher quality than that of a regular funeral home,” she says. “It has to be, since the bodies are being prepared for a longer time period than just a funeral and burial.”

The morgue and the gross anatomy lab are located in the basement of the new medical school building, which opened in 2007 and incorporates Emory’s historic anatomy and physiology buildings. The curriculum has been modified to include more patient interactions earlier for the medical students, but the gross anatomy course has long been required of first-year medical students, as well as physician assistant and anesthesiology assistant students.

“It was that way when I was in medical school and when my dad was in medical school,” Whitaker says. “It’s tradition—baptism by fire.”

The 132 medical students in the Class of 2011, as well as two oral surgery students, worked with twenty-two cadavers: three teams of two students paired with each.

“In the human anatomy lab in Thailand, the cadaver is called Ajarn Yai, the Great Teacher,” says Edward Pettus 89C, an instructor with the Department of Cell Biology who has taught gross anatomy lab at Emory for nearly a decade. “After all, the professors serve as mere guides for this educational journey. Body donors, individuals who donate their bodies to some unknown, nameless, faceless students, must feel a connectedness and a will to continue helping others as long as they possibly can. There is a strong sense of altruism and grace in this final act. Our donors are clearly compassionate givers, but I would also say that they are wise givers. I think they have donated to an incredible group of students who will take this gift and use it to its utmost.”

The lab itself consists of twenty-six stainless steel tables, each with a cadaver enclosed in a blue body bag. White lab coats hang on hooks on the far wall. The room is kept at a constant 65 degrees. A human skeleton hangs nearby for easy reference.

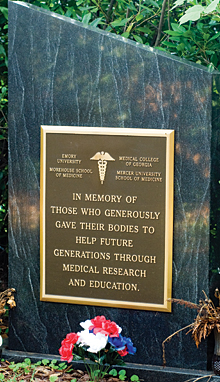

First-year medical students Laura Perry and Stephen Vindigni at Decatur Cemetery, where a monument honors those who donated their bodies to medical programs at Emory, Morehouse, Mercer, and the Medical College of Georgia.

Bryan Meltz

“I had never seen a dead body before, let alone cut into one,” says Andrew Banooni 11M, who has gathered with a small group of first-year medical students in a sunny, open atrium in the medical school building, just one floor above the cloistered anatomy lab. “Initially, I was overwhelmed by the gravity of what I was doing. Confronting my own mortality was perhaps the most difficult part. The face, hands, heart, and brain—those parts of the body most involved with the soul—had the most meaning to me.”

The students came to know very intimate things about the cadavers: surgeries they’d had, illnesses they died from, ailments that had probably not even been diagnosed during their lifetimes. They discovered artificial joints, glass eyes, brain tumors, cancers, dentures.

The bodies’ secrets were revealed, but not their identities.

“You don’t really know who they were, what their lives were like, what kind of car they drove, where they lived. It’s frustrating,” said Robert Beaulieu 11M. “But it would also be a huge emotional burden if you knew about them as an actual person.”

The only information provided to the students is the donor’s age, date of death, and cause of death. In lieu of real names, almost every table provided “their” cadaver with a nickname that seemed appropriate: “Big Guy,” “Gertrude,” “Ned.”

“We talked for a long time about what to name him,” says Laura Perry 11M. “None of us knew a Ned, it was short and sweet, and he kind of looked like he could have been a Ned.”

Body donors provide an amazing gift, said Steve Vindigni 11M. “Even surgeons don’t get to see the body in this depth,” he said. “We don’t know much, but we know that these were generous people.”

The concept of body donation is so profound that to the students it seems the ultimate act of altruism, with no expectation of personal gain.

“The strongest relationship we have is that with our own bodies. Our self-identity is our physical presence,” said Perry. “But through the lab, I realized how little I knew about it. I never visualized all these things inside myself, never thought about what I looked like or felt like inside. I can only assume that the donors made this gift thinking about the work I’m going to do with my future patients—looking out for the broader good.”

Banooni said the level of respect he has for his donor is so high, and he learned so much from him, that “I almost feel unworthy.”

The black granite monument at Decatur Cemetery honoring those who donated their bodies to medical programs at Emory, Morehouse, Mercer, and the Medical College of Georgia.

Bryan Meltz

“But you have your charge now, your responsibility, to use what you learned,” said Beaulieu. “It’s a pay-it-forward gift.”

Griffin Baum 11M, president of the medical school’s Class of 2011, said this is the basis of medicine: the passing down of knowledge from one generation to the next, those who come before teaching those who follow. “Body donation is the ultimate iteration of that. You can no longer teach with your words or actions—all you have left is your body.”

The human body is perhaps the oldest, most sacred teaching tool of the medical profession, but human dissection has had a somewhat troubled history.

Ancient Greek physician Galen of Pergamon drew sketches of the human anatomy inferred from animal dissections, since human dissections were forbidden by Roman law—although he did have the chance to make some direct observations of human anatomy by serving for several years as a physician in a gladiator school. He is said to have called wounds “windows into the body.”

The first comprehensive anatomy text was De Humani Corporis Fabrica (The Fabric of the Human Body), written by Renaissance Flemish physician Andreas Vesalius in 1543 and illustrated with elaborate wood block engravings. Subjects were hard to come by for Vesalius, as well, and he often resorted to stealing the bodies of criminals who were hanged near Paris, taking them home and dissecting them.

An original copy of Vesalius’s rare and famous anatomy guide, in fact, resides in the Woodruff Library’s Special Collections, and cost $300 when professors and students chipped in to buy it in 1930. Today, similar copies sell for about $100,000.

In seventeenth-century Europe, educational dissections were open to the public and often attracted crowds, who sometimes jeered and joked. In 1878, according to the New York Times, the body of Senator John Scott Harrison (son of President William Henry Harrison) disappeared from its Cincinnati crypt only to turn up in the dissection laboratory of a local medical school.

“The nature of the relationship between medical students and cadavers has changed remarkably over the last few decades,” says Paul Root Wolpe, director of Emory’s Center for Ethics. “There is much more respect for the cadavers and an appreciation for the sacrifice made by people who donate their bodies.”

Today, technological advances make it possible to see detailed imagery of the body and its inner workings on computers, which are positioned by each work station in the anatomy lab along with texts, lamps, stools, and dissection tools. Even De Humani Corporis Fabrica can now be found online and in CD format.

Each team also receives a “bone box”—kits filled with disarticulated human bones—to take home and study, another way of becoming intimately familiar with the mete and measure of the human body. The sheer volume of memorization required can be intimidating: The body has about six hundred named muscles that move about two hundred joints, and more than two hundred bones, not to mention the organs, nerves, circulatory system, and other structures.

During exams, the students answer questions about the cadavers such as:

5. The structure that passes through the marked opening is the:

A. aorta

B. esophagus

C. azygos vein

D. inferior vena cava

E. sympathetic trunk

Some schools have tried just using simulations, but “they come back to real bodies after a year or two,” Cooper says. “I don’t want someone working on me who has only worked on a computer.”

The students agree, saying that nothing is as powerful as direct experience. “You can touch a nerve and say, ‘This one little strand allowed a person to speak, or allowed the heart to keep beating,’ ” Vindigni said.

The anatomy lab is a place where “the magnificence of the human body becomes clear and med students learn reverence for, we might say, their first patient,” writes Albert Howard Carter III, a professor of literature at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida, who spent a semester observing first-year Emory medical students to write First Cut: A Season in the Anatomy Lab (Picador, 1997).

Carter was inspired to write the book after his father, a body donor, died and was sent to a medical school 150 miles away. He wondered: “What happened to his body? Whom did it serve?” After spending sixteen weeks with medical students in the lab, Carter made the decision to donate his own body.

“When the time for my death comes,” he writes, “I can think of no higher purpose for my muscles and bones, blood vessels and nerves, skin and, yes, even fat, than to send them to a human anatomy lab. I plan for my body to travel to a medical school where a young person, with a scalpel in hand (and perhaps heart in throat) will make a life-changing first cut.”

At the end of the gross anatomy lab in June, the students hold a ceremony of gratitude and the cadavers’ bodies are cremated. The cremains are then buried in one of ten congruent gravesites in a shaded grove in Decatur Cemetery, marked by a black granite monument that reads: “In memory of those who generously gave their bodies to help future generations through medical research and education.”

The families who wish to—about 65 percent, according to Cooper—can have a portion of their loved one’s ashes returned to them before burial.

Senior Associate Dean Bridgette Young extends a “ministry of presence” to first-year medical students who have questions about spiritual or moral issues in anatomy lab.

Jon Rou

As difficult as some aspects of anatomy lab are, says Senior Associate Dean of the Chapel and Religious Life Bridgette Young, valuable insights are gained. One of the first, she says, is achieving a state of acceptance and gratitude to the donors, living and dead.

“Students have to find a balance between the personal and impersonal, between seeing the human being who provided this meaningful and important gift and disconnecting in order to get through the course dissections,” says Young, who for eight years has been an adviser to first-year medical students taking the gross anatomy course.

Colleagues in traditional parish ministries are stunned when Young tells them of her service in the anatomy lab.

“It’s a ministry of presence, particularly,” Young says. “I’ve seen every part of the human body. It’s not something I ever thought I’d get used to. But this experience, working with these students in the lab, has turned out to be one of my favorite things.”

She engages them on matters of spirituality and morality that emerge from their work with the cadavers—difficult dialogues, but ones she refuses to shy away from. “Every year I’m asked, ‘Do you think these people really knew what was going to be done with their bodies, and what an incredible gift they gave?’

“Students are connected to the humanity of that person through their own humanity,” she says.

Although Young is not there as a professor or a student, the lab and its donors have transformed and taught her as well.

“As a parish pastor, I’ve officiated at a number of funerals,” she says. “The pat answer is always that the spirit lives on, but the body is just a shell. But after being in that anatomy lab, I can’t say that anymore. The human body itself is really complex and miraculous.”