Summer 2008: Of Note

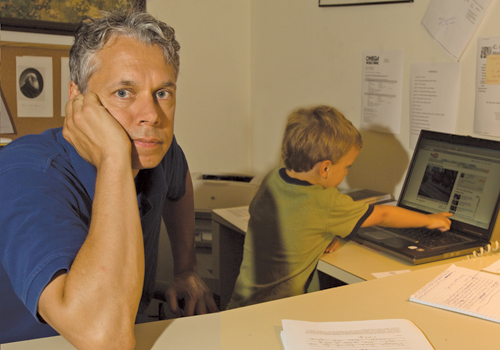

parenting unplugged: The father of a three-year-old, Bauerlein suggests unplugging as a family for at least an hour a day.

Bryan Meltz

Dumb and Dumber?

English Professor Mark Bauerlein takes on Generation Y in his new book

More on The Dumbest Generation

By Paige P. Parvin 96G

What’s the matter with kids today?

That question certainly didn’t originate with the 1960 Broadway musical Bye Bye Birdie, although the show did set it to a catchy tune. Every generation in human memory, it seems, has despaired of the next, shaking their heads at the inanity of youth and bemoaning the fate of society when the youngsters of the day grow up to take the reins.

But each crop of whippersnappers bears its particular brand of folly, and just because it’s old hat for grown-ups to criticize doesn’t mean they don’t have a point. Professor of English Mark Bauerlein offers his critique of kids today in The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future (Or, Don’t Trust Anyone under 30).

As the title suggests, Bauerlein focuses heavily on the pitfalls of the digital age, but his issue is not with the quality and availability of technology to young people—rather, it’s what they do with it. In an age when knowledge is more readily accessible than ever before, Bauerlein says, young Americans are appallingly ignorant of significant events both current and historic. According to a 2008 study by the United States Department of Education, for instance, more than half of seventeen-year-olds have no idea the Civil War took place in the second half of the nineteenth century. And on the 2006 National Assessment of Educational Progress history exam, two-thirds of high school seniors could not explain a sign on a theater door reading “Colored Entrance.”

What they are interested in is each other, constantly texting, calling, and messaging among themselves as they check their Facebook and MySpace pages and update their web blogs for their friends to read. The siren song of technology is nothing new, but for this generation, Bauerlein says, it never stops singing—beeping, ringing, buzzing, and chiming at all hours of the day and night.

Speaking at a park where he is watching his three-year-old son play, Bauerlein says, “TV has been doing this for decades, and video games have been around for twenty-five years, but we have taken a big step beyond what those things did. The digital age is creating a generational intensification of peer-to-peer contact that was never so extensive before. When I was fifteen, I would hang out with my friends at school, play basketball, and then go home, and when I crossed the front door, social life was over. Now there is no stop to social life. It goes on at midnight, in bed with the laptop or the cell.”

If that’s what teens are doing, what is it they’re not doing? Reading, most notably. In 2004, Bauerlein served as director of research and analysis for the National Endowment for the Arts, where he led a study that revealed a sharp downturn in leisure reading among Americans and young people in particular. That study raised his awareness of some troubling trends and laid the foundation for The Dumbest Generation (a term used by Philip Roth in his 2000 novel The Human Stain).

From an early age, reading—whether for fun or for homework—is critical to building vocabulary, Bauerlein says, and children who live in homes with few books and newspapers are at a serious disadvantage. Vast vocabulary acquisition happens early and fast, and as kids progress to the upper grades it becomes difficult to make up for lost time.

“Often those kids come into kindergarten with a two-thousand-word vocabulary, and they are in the same room with kids with a six- or seven-thousand word vocabulary,” he says. “At that point, the teacher can do very little to make up the difference. That’s their fate from then on.”

That fate hobbles them into college and beyond, as the nation’s employers increasingly complain that recent college graduates do not have the verbal skills necessary for success—and not just in the corporate world. Even the National Association of Manufacturers has reported that young employees struggle with the reading required for various work, according to Bauerlein. “Only in really abstract areas can we say those verbal deficiencies don’t cause serious problems,” he says.

While it’s true that youth are quick to embrace new technology, often leaving their elders shaking their heads in dazzled admiration, it’s not necessarily improving their verbal skills, content comprehension, retention, or critical thinking, Bauerlein says—quite the opposite. Studies show that students reading online do not read in depth, but skim the screen for key messages and block out the rest, quickly forgetting what they absorbed in the first place. They are increasingly unable to distinguish credible sources from those less worthy. Digital communication doesn’t foster correct grammar or superior sentence structure, but abbreviated phrases like “OMG, r u there?” And although an astonishing array of educational resources is available on the Internet—literature, science, history, art, world newspapers—kids aren’t interested. Facebook and MySpace are hands-down their favorite sites, with some 100 million members each.

It’s tough to say what these trends will mean for society and culture in the long term, but in the short term, Bauerlein says, there is plenty adults can do to put young people back in touch with living, breathing reality. For one thing, parents can establish one hour each day, perhaps after dinner, in which the entire family unplugs, sits together, and reads.

What’s at stake, Bauerlein insists, is our very way of life. There is a strong correlation between reading and civic participation, and young people’s engagement in civic life and the democratic process is at an all-time low, with 45 percent failing to understand an election ballot.

“Democracy puts a heavy knowledge burden on its citizens,” he says. “I’m not antitechnology, but I am against uses of technology that disconnect adolescents from learning and becoming mature, informed citizens in a democratic society. Young people need to realize that the great ideas and beliefs and actions and events and words are really the materials of character formation, not just of fulfilling a course assignment.”

The Dumbest Generation has created considerable buzz in major media outlets around the country, earning Bauerlein provocative headlines, radio interviews, and TV appearances on C-Span, CBS News, and ABC News. The New York Times called the book “brisk and engaging,” saying, “Full of stats and charts, his book is like a Power Point presentation you can actually stay awake for.”

Not surprisingly, the book has its share of detractors as well. An article in Newsweek finds reason to be more optimistic about Generation Y, saying, “Oddly, Bauerlein acknowledges that ‘kids these days are just as smart and motivated as ever.’ If they’re also ‘the dumbest’ because they have ‘more diversions’ and because ‘screen activity trumps old-fashioned reading materials’—well, choices can change, with maturity, with different reward structures, with changes in the world their elders make. Writing off any generation before it’s thirty is what’s dumb.”

Some of Bauerlein’s sharpest critics are members of the dumbest generation, such as a reader who wrote to the Boston Globe in response to the book: “Calling my generation dumb is the generation that went to Woodstock and smoked weed and did acid. Do you honestly think the generation before them didn’t see a problem with that?”

But Bauerlein has no problem with criticism and intergenerational debate—in fact, he finds it refreshing, even hopeful.

“As the generation that grew up in the sixties, we need more rebuke of the young,” he says. “And we need more young people to get angry, work harder, and prove the adults wrong.”