Spring 2008: The Creative Campus

Kay Hinton

Rushdie Hour

Distinguished Writer in Residence Salman Rushdie is living proof that books can change your life

By Mary J. Loftus

Salman Rushdie

Jon Rou

Rushdie to appear in Atlanta

Salman Rushdie will speak about his new novel, The Enchantress of Florence, at The Carter Center on July 7 at 7:00 p.m. in partnership with A Cappella Books. For ticket information, visit www.acappellabooks.com.

In early autumn 2004, a party was in full swing on the stone patio of Lullwater House. A band was playing the blues, trustees, professors, and graduate students were laughing and milling about, and a margarita fountain was casting an inviting green glow on a corner table.

Emory’s presidential home looks resplendent in the fall, a Tudor-Gothic castle surrounded by wild roses and fallen poplar leaves. The place makes such an impression that, after viewing Hale-Bopp from the house’s turret in 1997, visiting Irish poet Seamus Heaney was moved to write “The Comet at Lullwater.” Celebrities, scholars, and dignitaries of every ilk—Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, Desmond Tutu, Christiane Amanpour, the Dalai Lama—have been fêted here.

But this night, this party, was a courtship dance, and the crowd revolved like a Gravitron ride around one guest: the bearded, bespectacled, and slightly bemused man standing over by the band—Salman Rushdie.

Living up to his devilish, Jack Nicholson-esque appearance, Rushdie exudes a powerful charisma with his erudite mind and wry wit. His public talks—one of which he had just finished delivering a few hours before to a packed house at Glenn Memorial as part of Emory’s Richard Ellmann Lectures—are appreciated for their intelligence, humor, and frequent irreverence.

It seems to be an irresistible combination. Rushdie was, at the time, married to the stunning cooking show host Padma Lakshmi (they’ve since divorced) and had been attached to three previous wives, all noted for their beauty and talent. But he had never permanently attached himself to a university. Could Emory tempt him to pack up his boxes and settle his archives here?

He seemed receptive to beginning the conversation, says Steve Enniss, director of Emory’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL). Rushdie felt that he was in good company with previous Ellmann lecturers Henry Louis Gates, A. S. Byatt, David Lodge, and Heaney, who placed a major portion of his archives at Emory.

“The fact that Rushdie had come to the University as part of the Ellmann lecture series, which set a very high bar for literary excellence, was fortunate,” Enniss says. “Rushdie did not know Emory, but he knew that this was a place where the literary arts were appreciated. And, I think he began to feel that Emory was a hospitable place for him, personally.”

Distinguished Writer in Residence Salman Rushdie leads a lively forum with Emory students, including (from left) Eric Betts 09C, Christie Pettitt-Schieber 09C, and Nora Kleinman 08C, about science fiction, the nature of truth, and the higher meaning of rock and roll.

Brett Weinstein/The Emory Wheel

Four years later, Rushdie—now an Emory Distinguished Writer in Residence—is nearing the end of his annual month-long stay at the University.

“So far, so good,” answered Rushdie recently, when asked how things were going. “Last year when I was here, I found the seminar I was teaching very pleasurable because the quality of students was very high. And it’s just as lively this year as last. The one thing I was most worried about was that I wouldn’t be able to do any of my own work, and that would start driving me crazy. I discovered to my delight that actually the opposite was true, and that I found myself able to work really well.”

He is soon to embark on a book tour for his latest novel, The Enchantress of Florence, a sizable portion of which he wrote while here. The novel is set in sixteenth-century India and high-Renaissance Florence. His graduate assistant at Emory, Rebecca Kumar, was assigned the task of finding out “all the rude words that people used back then,” says Rushdie, smiling. “If people got angry, what did they call each other? All the swearing in the novel is down to Rebecca.”

On a chilly Monday in February, Rushdie is dressed in a pink shirt with an open collar and a black suit, and is talking animatedly with a room full of students in the Visual Arts Building. It’s a diverse group, including religion, film, English, business, and art history majors.But the renowned Indian-born author—whose life was hijacked for a decade by death threats from Islamic extremists for perceived blasphemy in his book The Satanic Verses—can hold forth on nearly any subject, from science fiction and the nature of reality to William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac.

Christina Welsch 10C, a history major, asks Rushdie about the genre of fantasy fiction.

“In fantasy, fiction is often a vehicle for intellectual or philosophical exploration—it’s quite often a literature of ideas,” says Rushdie, whose debut 1975 work, Grimus, was a blend of science fiction and folklore. “The actual writing is not as good as the imaginative effort behind the writing. Quite often the ideas are rather wonderful but their expression is not. The exceptions to this are rather famous because they are such good writers . . . like Bradbury or Philip Dick or Vonnegut. It’s like an oasis in the desert, really. And I think all those writers to some degree have transcended the form because they write too well for it.”

Rushdie clearly enjoys himself in a professorial role. His speaks deliberately, his right hand keeping pace with the rhythm of his words, and seems to relish the moments when his amusing asides provoke laughter. Often he begins with one topic and ends up at quite another.

When Rachel Rosenberg 09C, a religion major, asks about the nature of truth, Rushdie jumps from discussing Edenic states of grace to the idea of “hard-wired” morality to universal rights.

“I think in order to create a livable society . . . you basically need two things: freedom of expression and the rule of law,” he says. “Without rule of law, you get warlords and gangsters, and without freedom of expression, you can’t have any of the other freedoms. Why have freedom of assembly if you can’t say what you think? The reason I think that’s a universal right is because we are a language animal. We are an extraordinarily verbal, linguistic species, which explains itself, discusses itself, understands itself, through the use of language.”

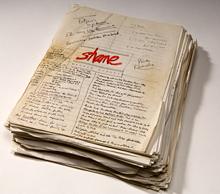

If we are a linguistic species, some would say Rushdie embodies our next evolutionary leap. His novels, including Midnight’s Children, which won Britain’s highest literary honor, the Booker Prize; Shame; The Moor’s Last Sigh; The Ground Beneath Her Feet; Fury; and Shalimar the Clown, have been called “rollicking comic fables,” “feasts of language,” “biting parables told at breakneck speed,” and “bright streams of words.”

His current project is reported to be a children’s book conceived for his ten-year-old son, Milan, who, after discovering that his older brother, Zafar, had a novel written for him (Haroun and the Sea of Stories) asked his father, “Where’s my book?” Rushdie said it seemed “only fair” to comply.

“The experience of loving a book is something that we all have,” he tells the students, near the end of the forum. “Maybe we don’t have it that often—the number of books you really love in a lifetime might be relatively small—but this is how literature actually changes the world, one person at a time. Those books leave behind something of the residue of how that artist saw the world, and it becomes part of how you see the world.”

“I see Salman Rushdie as a storyteller who’s devoted to telling stories across cultures, across time, across belief systems. He connects the dots between people, places, and times. With his appointment, and placing his archives here, his story now becomes a part of Emory’s story. And Emory’s, I hope, a part of his.”—Rosemary Magee 82PhD

Kay Hinton

Bringing Rushdie’s vision of the world to Emory was the result of complex negotiations that began with the Ellmann lectures and were conducted through his New York agent, Andrew Wylie.

Wylie is known in literary circles for driving a hard bargain. His top clients, living and dead, include Martin Amis, Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, Susan Sontag, Philip Roth. Wylie has said he tries to get the best financial arrangement possible for elite writers, who he believes deserve as much money as commercial writers, and seldom discloses—at least to the press—the details of such deals. He likes to quote Rushdie in saying that some things are “P2C2E,” which stands for: “Process too complicated to explain.”

“A lot of factors were involved,” says Enniss of the acquisition, which took eighteen months. “For several months, it wasn’t clear whether we’d be able to come to an agreement. Then, there was a point when I realized we were going to make this happen.”

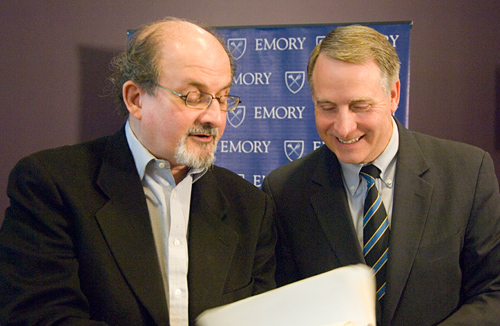

On September 9, 2006, the deal was struck. Rushdie would not only place his papers at Emory, he would be appointed a Distinguished Writer in Residence, spending a month each year for five years teaching and lecturing at the University. “These are living archives in the genuine sense that Emory received not only the papers, but actually the author himself,” says Emory College Dean Robert Paul. “This makes us present at the creation, and not simply the recipient of the remains of past creative work.”

Rushdie with President Jim Wagner.

Jon Rou

The handshake that followed was felt round the world, making headline news in New York, India, and especially the U.K., where the press expressed concern that “Britain’s literary heritage is being lost to foreign buyers.”

Ahmed Salman Rushdie was born in Bombay (now Mumbai), but was educated in Britain, studying history at Cambridge, and lived there during his years spent in hiding. Britain and India both claim him as their literary son, but Rushdie says he is a man of many places—one of the globe’s migratory masses who “begin in one spot and end up in another.” He considers himself at home in cities from Mumbai to London to New York.

In late October 2006, Enniss traveled to London to help pack up Rushdie’s papers and to practice a bit of international diplomacy. As luck would have it, the British Library had organized a conference, “Manuscripts Matter: Collecting Modern Literary Archives,” at which both Enniss and Goodrich C. White Professor of English Ron Schuchard had been invited to speak, and Enniss expected some fallout.

“When I arrived in London, BBC’s Radio 4 called me for an interview with the current poet laureate Andrew Motion [a vocal proponent of keeping British authors’ archives in British institutions], and I think some people hoped that sparks would fly,” Enniss recalls. “But actually, we had a quite civil conversation, and Motion was complimentary about the value of having the archives available to students and scholars.”

After a day of packing and boxing with a London bookseller in Rushdie’s home near Portobello Road, Rushdie, Enniss and his wife, Lucy, and Schuchard and his wife, Keith, went out to London’s Launceston Place for a celebratory dinner, complete with champagne. “I’m not sure what emotions Salman was feeling,” Enniss says, “but certainly those of us from Emory realized the significance of what had been accomplished.”

Rushdie’s archives are now securely ensconced on the tenth floor of the Woodruff Library, in MARBL special collections. “One of the motives in my case,” Rushdie says, “was to find them a safe home. Steve can tell you the condition the boxes were in. Frankly, I thought the papers would probably be in better hands here than with me.”

Still, Rushdie sometimes bemoans the fact that readers today seem to care more about the novelist than they do the novel itself. In a public lecture on “Autobiography and the Novel” in February, Rushdie pointed out that, during the time of Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver’s Travels, and Tristram Shandy, it was possible for “books to become celebrated while authors stayed in the shadows. Fiction was fiction, life was life, and 250 years ago people knew these were different things. We now seem to believe that the only way of understanding a text is to understand the writer’s life.”

Rushdie finds it off-putting to be asked, as he quite often is, “How autobiographical is this novel, or this character?”—even though many of his protagonists seem to reflect at least some aspect of Rushdie himself, and the settings are often places he knows intimately though birth (Bombay), boarding school and university (London), or choice (Manhattan).

Like the protagonist in Midnight’s Children, Saleem Sinai, Rushdie was born in Bombay in 1947, the year that India claimed its independence from Great Britain. And like the narrator of Fury, Professor Malik Solanka, he has lived in New York City while dating a gorgeous woman with a scar on her upper arm.

There will be no more “me” characters, he told a rapt audience during the February lecture: “Too much of my life story has found its way into the public consciousness already. I’ve learned my lesson.”

Nevertheless, he admits to sharing some of this same biographical curiosity about his favorite authors, calling it a “form of higher gossip.” Rushdie even took a road trip with Vice President and Secretary of the University Rosemary Magee 82PhD and Enniss to Milledgeville, Georgia, where he toured Flannery O’Connor’s farm, Andalusia.

“Probably the cruelest short story in the English language is O’Connor’s ‘Good Country People,’ ” he said. “And to be able to be shown the barn, which was a setting in the story—well, if you’re a writer, you’re interested in that stuff. To see the source material.”

So instead of burning his papers, which was perhaps his first instinct (“I admire those authors who destroy their archives,” he says), Rushdie sent them to Atlanta. While the prospect of strangers rifling through his papers alarms him a bit—he once compared it to people going through his underwear—he also admits that it will be “incredibly helpful to have this material properly catalogued.”

The University acquired the Rushdie archives for an undisclosed sum, but the scholarly value of such resources to research institutions is undisputed. The well-supported Ransom Center of University of Texas at Austin bought Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s Watergate notebooks in 2003 for $5 million, and Norman Mailer’s archive in 2005 for $2.5 million. Allen Ginsberg’s papers sold to Stanford in 1994 for just over $1 million. “How such papers change hands—and find monetary value—is the result of a peculiar alchemy between market forces and literary reputations,” wrote Rachel Donadio last year in the New York Times Book Review.

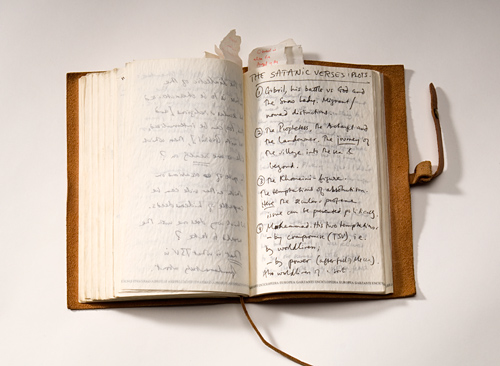

A journal from the archive.

Kay Hinton

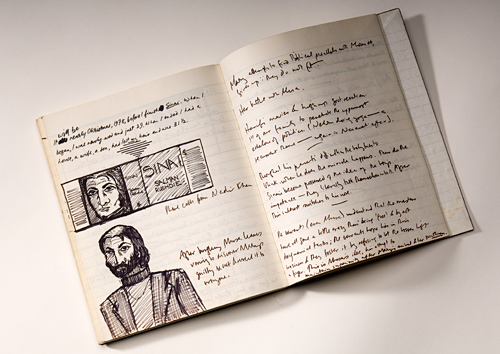

Rushdie’s papers include his early writings, two unpublished novels, and a first manuscript of Midnight’s Children. They also contain personal journals he kept to detail his life in hiding under the fatwa, a religious edict issued by Iran’s late leader Ayatollah Khomeini on Valentine’s Day of 1989, condemning Rushdie to death (and placing a price of 1.5 million pounds on his head) for what some Muslims said was blasphemy against Islam and the prophet Mohammed in his 1988 novel The Satanic Verses.

In addition, the Rushdie archive includes four of his computers, making it the first, but certainly not the last, archive Emory has acquired with significant amounts of digital data. The computers include one early Mac desktop, three Mac laptops, and one external hard drive, and contain data (including email) from the late 1980s to the present.

“We have to figure out how to present this material to researchers in a way that capitalizes on the rich potential of this digital content, while honoring and living up to the agreements and restrictions of the donor,” says librarian Erika Farr 04PhD, the digital program team leader. “It’s an interesting line to walk.”

Select digital materials will be printed out and integrated into the paper archive, she says, but “there’s always a danger, when pulling content, of stripping away the context. Future researchers will be interested in both. My dream would be to make the digital archive available in a virtual environment—the user could go into the computer as if they were Rushdie, sitting down to go to work on his computer.”

While some of the paper archive—journals, diaries, drawings, and early writings—already are available for public viewing in glass cases on the tenth floor of the Woodruff Library, Rushdie’s digital archive (which contains more than 40,000 files and 18 gigabytes of data in total) will probably be released in phases over the next two years, Farr says. “It was astonishingly brave of him, really, to hand over all this information,” she adds.

A university like Emory is in many ways a natural environment for Rushdie, says Associate Professor Deepika Bahri, director of Emory’s South Asian Studies Program, who grew up in Calcutta and knows the author well. “He has a generous mind and is always looking closely at the world—analyzing, assessing, laughing at it and at himself,” says Bahri, who, when Rushdie was in Atlanta, invited him over for a dinner party with a few friends for a traditional, home-cooked meal. “He always has a great story to tell. He’s very present here at Emory—to students, faculty, people he meets while walking across the Quad—in every sense of the word.”

Sometimes, Bahri and Rushdie will slip into Hindi or Urdu while speaking—the languages of their homelands, their childhoods. “He’s very funny,” she says, smiling. “He’s very funny in any language.”