Spring 2008: Cover Story

Students get creative at the annual student arts festival.

Kay Hinton

The Creative Campus

The transformative power of the arts is being championed across disciplines, filling empty spaces with fresh visions

By Mary J. Loftus

Salvador Dalí’s surreal paintings melt across the screen, seductive and disturbing, like disjointed fragments of fleeting dreams.

Justine Phifer 08C is showing PowerPoint slides of the artist’s work as part of a presentation on Dalí for the senior seminar Personality and Creativity.

“His brother, also named Salvador, died nine months before he was born, and his parents took Salvador to his grave when he was five years old and told him he was the reincarnation of his brother,” she tells the class.

Phifer highlights various aspects of Dalí’s life: his mother died, and his father married her sister, Dalí’s aunt; he was expelled from art school because he had said there was no one there “worthy of evaluating his work”; he married Gala, a Russian immigrant eleven years older than he, and was with her until his death. Phifer clicks on a link to a YouTube video of large plaster eggs on a beach, and the class laughs as Dalí and Gala dramatically emerge together from one of the shells—early performance art.

Professor of Psychology Marshall Duke opened the class discussion about Dalí by saying that, like Sigmund Freud, he appeared to be “the chosen one” in his family. And, like many artists, the loss of a parent at a young age seemed to drive him “to live two lives.”

“So was Dalí a big ‘C’ creative—someone who does something we notice and value, that transforms the world?” Duke asks. The collective answer seems to be yes.

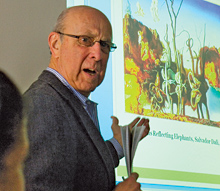

art with edge Professor Marshall Duke leads a seminar on personality and creativity.

Kay Hinton

Duke recounts a humorous story about Dalí showing up at a party in New York City in full scuba diving suit and gear.

At the end of class, as students gather their creativity projects and prepare to leave, Duke mentions several recommended readings, including a piece in the New York Times Magazine about a pyrotechnic artist.

“I know many of you are overwhelmed right now and want someone to tell you how to think about all of this,” he says. “There’s a reason this is a senior seminar. You’re preparing to enter the real world. And in the real world, there is no syllabus.”

Creativity and the arts are among Emory’s signature initiatives, says President Jim Wagner, thanks to the “critical role of the arts in sustaining free societies and in confronting oppression.”

“Even as the health sciences push back the boundaries of our understanding of what it means to be biologically alive, we must ask the arts and the humanities to help us define what it means to be fully, humanly alive, to live in community, to understand our souls and to express ourselves,” Wagner says. “That’s a tall order, but one that Emory must invest in. It is fundamental to what we are attempting to become.”

Testaments to this commitment abound. Perhaps the most significant celebrates its fifth anniversary this year: the Donna and Marvin Schwartz Center for Performing Arts, which since its opening in 2003 has become one of the busiest buildings on campus. Made possible by a cornerstone gift from Donna Keesler Schwartz 62C and her husband, Marvin, the Schwartz Center has reshaped and enhanced the arts at Emory in untold ways, says Sally Corbett, director of communications and marketing for the Emory College Center for Creativity & Arts. Signature arts programs such as the Emory Coca-Cola Artists in Residence have attracted more visitors and student interest than ever before.

“The number of music majors has doubled since the facility opened,” Corbett says. “It’s an integral part of the core melody of campus.”

Vice President and Secretary of the University Rosemary Magee 82PhD, who was instrumental in the creation of the Schwartz Center, recalls an inspiring moment a few years ago when she was waiting for a light to change at the corner of North Decatur and Clifton roads. “Housed within a stone’s throw from each other were buildings for religion, law, business, health sciences, humanistic inquiry, Russian and East Asian languages, and the performing arts,” she recalls. “This crossroads fully epitomizes Emory’s mission to help men and women fully develop their intellectual, aesthetic, and moral capacities.”

Indeed, in addition to the Schwartz Center, creative spaces thrive across campus, from the Burlington Road Building to Glenn Auditorium, the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Cannon Chapel, Mary Gray Munroe Theater, and Oxford’s Tarbutton Performing Arts Center. The recently expanded Visual Arts Building showcases one of the fastest-growing programs in Emory College, which developed from a small studio program into a burgeoning enterprise in newly expanded space with a gallery showcasing acclaimed exhibitions.

But art is not confined to a building or a place, Magee adds: “Art surrounds us—sometimes even catches us by surprise.”

Increasing the presence—both physical and intellectual—of art on campus is certainly the aspiration of the newly formed Emory College Center for Creativity & Arts. This ambitious effort, nurtured alongside the Creativity and Arts Strategic Initiative, already has leafy tendrils spiraling out like fast-growing ivy.

The center will support myriad creative endeavors, often in unexpected ways, according to executive director Leslie Taylor, chair of theater studies—all to encourage people to “see things fresh.” Plans include commissioning an artist for an upcoming conference on evolution, issuing the “Emory Arts Passport” and “Out There Arts” grants for easier access to arts events, and providing grants for artistic research projects. The center has physical loft space off North Decatur Road, near the Schwartz Center, where visiting artists can work and informal discussions between artists and students can take place.

“A sea change has happened in my time at Emory,” says Taylor. “The artistic disciplines are now viewed not just as entertainment, but as collaborators, as valued parts of the University and college that have something to add to the body of knowledge.”

Playing a supporting role Associate Professor Leslie Taylor directs the Emory College Center for Creativity & Arts, designed to support innovative efforts.

Bryan Meltz

Randy Fullerton, general manager of the Center for Creativity & Arts as well as a member of Emory’s public art committee, hopes to see more works of art showcased around campus and arts advocates in every department of the University. “Creativity and the arts really is the overarching theme that binds all the disciplines,” he says.

Expanding Emory’s public art offerings—such as the newly installed sculpture in front of the Schwartz Center, Jose De Rivera’s Construction #200, recently donated by Donna and Marvin Schwartz—is a great way to bring art into community life, agrees Katherine Mitchell, a senior lecturer in arts history. Exceptional art then becomes part of the surroundings, she says, “something to be enriched by, even as we just move across the campus in our daily routines.”

Winship Chair of the Arts and Humanities James Flannery, who founded Emory’s theater department in 1983, says talent and collaboration are at the root of most artistic endeavors, but an appreciation of the arts—both high and low—must be broadly supported. He advocates future projects that “capture the imagination, intellectual respect, and attention of the whole campus community and beyond,” including an Emory Arts Festival, a University Art Bank, and a scholarship program to recruit exceptional students in the arts.

Providing the props

A gaggle of faculty members are gathered around boxed lunches in the Jones Room of the Woodruff library, fixedly examining their pencils.

Some wiggle them, some twirl them, others scribble with them. Their assignment is to think of as many different uses for a pencil as they can in a few minutes. The answers come rapid-fire: “To write a poem.” “To make a fire.” “To conduct an orchestra.” “To advertise on.” “To bite.”

Workshop leader Steven Tepper, a Vanderbilt University sociologist and cultural scholar, was invited to Emory in early February to talk about the “creative campus” movement. “The three dimensions of creativity are fluency, flexibility, and originality,” he says. “So how many of these answers are truly creative?”

A broad-ranging discussion on creativity in teaching follows, from creating engaging lectures to encouraging high-achieving students to reach beyond their comfort zones.

“How do you toggle back and forth between a safe place and a serious place?” Tepper asks. “How do you convince students that creativity is a risk worth taking?”

Senior Lecturer Holly York of the Department of French and Italian says she tries to rev up her classes with spontaneous exercises. “One of my favorite projects is a skit on Paris in French 201. The students are to imagine themselves enjoying Paris with friends when a sudden, surprising event takes place. They must show what this event is and, because of the event, go to three different areas of Paris, commenting and giving cultural information on each.”

Just before a performance, York will produce a “mystery bag” and ask the group to pull out an object—a wig, a large artificial flower, a plastic hand, a deflated beach ball, a stale loaf of French bread, an ugly high-heeled shoe, a teddy bear—that they are required to use in their skit. “The results are sometimes ingenious, often hilarious,” she says. “It’s not unusual for students who are normally the quietest in class to steal the show.”

Associate Professor of Physics Eric Weeks takes his introductory physics classes on “field trips” around the Math and Science Center to view sources of light through polarizers. Associate Professor of Theater Studies Michael Evenden produces wry PowerPoint presentations for his Theater History classes that, students say, remind them of “The Word” on The Colbert Report.

“A lively, creative campus is vital for attracting faculty and students and helping them to thrive,” Tepper says. “But this raises several questions: Can we teach creativity, or is it something that comes upon us in Eureka moments? Is Emory a place where creativity can and does flourish?”

The business of art The Goizueta Foundation Center boasts the Balser art collection, with works by Dali, Picasso, Rauschenberg, and Warhol.

Kay Hinton

After all, creativity has not always been viewed as a greater good—in fact, it’s sometimes seen as an impediment to productivity. “Creativity pushes boundaries, often with deviance and abandon,” Tepper says. “It is expressive, eccentric, original, innovative, dramatic, free-spirited, and cutting-edge. It means solving puzzles in unauthorized ways. It means students with blue hair. Creativity means controversy.”

Creative hubs, be they funky cities or artsy universities, are now attracting the most influential and successful people—including those with blue hair, according to Richard Florida, who wrote Rise of the Creative Class and is a professor of regional economic development at Carnegie Mellon University.

Americans are spending more money on entertainment and information than on tangible goods, says Florida, and the “creative” sector of the economy is growing three times as fast as the rest of the economy. Bohemian, diverse areas attract educated, highly skilled workers who want to live in places with street-level culture and sidewalk cafes.

Time for creativity?

While Emory strives to establish a collegiate version of this scene, it faces a powerful counterforce: very busy students, who have the will to be creative—but only when there’s time.

“There’s not really a ‘counter culture’ here or anything because there’s not really much to push against. Everyone is generally okay with everything,” says Nathan Green 08C, a theater studies major. “A lot of people say Emory is an apathetic campus, but I just think everyone is too involved with different organizations to sit around and come up with creative ways to do something outside of an organization—for better or worse. I would love to have more free time to do crazy stuff.”

Still, Green is a big fan of efforts such as Campus Moviefest, an annual event in which students are turned loose with video cameras to make films that then compete against one another.

And despite their busy schedules, Emory students merge technology with talent to get creative in their daily lives, often in ways unimagined a decade ago.

Wide-ranging examples include multimedia presentations, MySpace and Facebook photo galleries, “handmade” websites, art that incorporates video, and “sustainable” art using recycled crushed cans (as in the portrait in the Math and Science Center, 1440 Cans, by Ben Gadbaw 07C). It’s clear that contemporary creators aren’t limited to traditional materials like brushes and paints.

Professor of Music Steve Everett, who teaches electronic music and computer music composition and directs the Music/Audio Research Center at Emory, says technology can provide some impressive tools, but it can’t replace the interaction between people and artists.

For instance, “when people listen to music on a CD, I’d say they get about 20 percent of it,” he says. “That’s why students are willing to pay $60 to see their favorite performers in concert, even though they can download the songs for free.”

Visual artistry Alumnus Madison Dotson creates art that can be seen and felt, such as her textured embroideries of nudes that she calls “landscapes.”

Kay Hinton

At the same time, at any such concert, hundreds of cell phones snap photos and record video so the experience can be shared with others. Visual artist Madison Dotson 05Ox 07C, an intern with the Creativity and Arts Initiative, sees these possibilities all around her. Like many of her friends, Dotson practices “life capturing”—posting photos she takes on her cell phone into an online gallery. “My generation captures life at the speed that it happens,” she says.

Walking through a hallway on the second floor of the Schwartz Center, Dotson describes plans to use the space as a gallery for painter Kombo Chapfika 05C, who has been commissioned by Emory’s Society of Creative Scholars to do a triptych of his interpretation of Plato’s cave. “Why have an empty wall?” she asks.

Whether it’s fine art or Webcam creations, artistic expression can be discovered in dozens of creative hot spots on campus, including the Cox Hall Computing Center, the Quad, Oxford’s Williams Gym dance floor, the parlor of Dobbs Residence Hall, Emerson science labs, the Biomedical Research Building, Rich Building theater practice rooms—and even a particular apartment at the Clairmont Campus where the tenants host salon-style gatherings of arts and theater devotees.

“When you combine all of the research in the sciences and humanities with the visual and performing arts and ingenuity expressed by faculty, staff, and students daily, I would say Emory is a huge repository of creativity,” says Jason Najjoum 08C, a music and history major. “But I think we should work to have some cross-campus, organized creativity in the sense that we actively put creative people together from different fields.”

Art in daily life This graceful sculpture, Jose De Rivera’s Construction #200, was recently installed outside the Schwartz Center.

Kay Hinton

Undergraduates are doing their part to make creative synergy, double-majoring in—quite literally—both the arts and the sciences: music and neurobiology, dance and physics, theater and chemistry.

“Many students at Emory are brilliant,” says Christie Pettitt-Schieber 09C, a theater studies major, “and not just premed brilliant—they’re also brilliant violinists or pianists or actors, modern-day Renaissance men and women. They’re phenomenal additions to the experience of campus life because they struggle every single day to make those passions for science and art, which seem so natural to them, coexist together academically.”