Autumn 2007

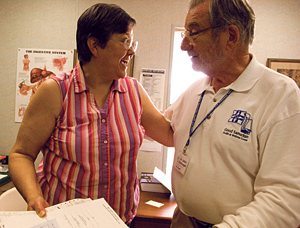

Ouch: Patient Gene Beck, shown with volunteer nurse Marty Beaver, is one of some four thousand patients who receive primary health care at “Good Sam.”

Kay Hinton

Health and Hope for Rural Georgians

A free clinic with Emory roots helps patients ‘hold on to quality of life’

By Paige P. Parvin 96G

Gene Beck sits straight on his chair in the tiny examining room, patiently submitting to the routine ministrations of volunteer nurse Marty Beaver. Brisk and cheerful, she checks his blood pressure. “Your BP is 205 over 104,” she scolds him. “Why is it so high today?”

Beck, a short, barrel-chested man with work-worn hands, a wide cowboy hat, and a belt with “GENE” stitched into the leather, pulls from his shirt pocket a grimy memo pad in which he has painstakingly recorded the names of his various medications. “I’m out of this medicine,” he tells her, pointing.

After spending more than twenty years behind the wheel of an eighteen-wheeler rig, Beck underwent quadruple cardiac bypass surgery in 2003. Now sixty-five, he works part-time driving a delivery truck and has taken a new interest in managing his health. “Gene is one of our star patients,” Beaver says proudly, adding that she and Beck attended high school together.

Beck is one of more than four thousand patients who receive regular care at Good Samaritan Health and Wellness Center, a free clinic in the rural mountain community of Pickens County, Georgia, population about 23,000. Founded five years ago by John Spitznagel, who chaired Emory’s Department of Microbiology from 1979 to 1993, and Al Hallum 58C 62M, along with a handful of others, the clinic has grown to fill a need even its visionaries could not have anticipated.

Semi-Retired: John Spitznagel (left) and Al Hallum 58C 62M founded Good Samaritan Health and Wellness Center five years ago in response to community need.

Kay Hinton

“Our church [Holy Family Episcopal Church] ran a food pantry, and everyone kept saying, ‘These people need medical care,’ ” Spitznagel says. “They have no money, no insurance. Many have bad teeth, which can prevent them from working. We would watch what they bought at the grocery store—all the wrong foods, tobacco products, and soda. Something was seriously wrong.”

So Spitznagel and Hallum began to lay the foundation for Good Samaritan. Pickens County gave them a plot of land, conveniently situated behind the public health department, and supporters raised money and donations, including several trailers.

“If you had told me that when I retired, I would be talking to politicians and raising money—two things I never wanted to do—I would never have believed you,” says Hallum, who served for much of his career as chief of obstetrics at Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital and later chief of staff at West Paces Medical Center.

Five years later, the clinic is a bustling warren of double-wides serving some seven hundred visitors a month—at no charge. A core volunteer staff of eight doctors offers basic medical care, dental care, eye examinations, X-rays, and lab services. A critical need at Good Samaritan concerns the drug assistance program; volunteers help patients complete laborious application forms so they can obtain needed medications. In 2006, the clinic pharmacy dispensed more than fifteen thousand prescriptions.

All this activity is supported by executive director Carole Maddux, a budget of $350,000, and nearly 350 volunteers, who perform tasks from escorting patients through their visits to providing child care to counting out pills in the pharmacy.

“A lot of our local volunteers are second-, third-, even fourth-generation families from Pickens County,” Hallum says. “Everybody here is here because we want to help, to give something back. We are able to do something of value for these people. It gives them a little better hold on some quality of life.”

Jackie Gilmer, a resident of nearby Big Canoe and a former staff member at the Emory Alumni Association, has volunteered with Good Samaritan since it opened.

“It has absolutely been a lifesaver for these people,” she says. “The stories of people getting their health back are just overwhelming.”

The patients’ most common ailments include hyptertension, diabetes, obesity, and respiratory illnesses; some 80 percent smoke. The physicians and other volunteers offer education when they can and also refer patients with mental illness to other local treatment facilities.

Hallum remembers a woman who had damaged teeth and always spoke with her hand in front of her mouth. Volunteer dentists at Good Samaritan were able to repair them, and the patient landed a job the next week.

“Often these small victories help people get back to work,” Hallum says.

Checking up: “You're looking so good,” Dr. Spitznagel tells patient Joyce Weaver. “Come back and see me in a month.”

Kay Hinton

One hot morning in July, patient Joyce Weaver visited Good Samaritan to get refills for her prescriptions. Weaver has high blood pressure and diabetes, and she has lost much of her kidney function as well as her hearing. A widow, she receives her late husband’s veteran’s pension, but it’s not enough for luxuries like cholesterol medicine.

“This place has helped me because I’m on a set income,” she explained. “All the prescriptions I need would be very hard to afford. It would be medicine or food, I guess.”

When it is Gene Beck’s turn to see the doctor, Spitznagel chides him for waiting too long to replace his blood pressure medication. “When you run out like that, you let us know,” he says. “Are you still working on the delivery truck? You’re not lifting heavy boxes, are you? Just the little stuff?”

It is clear from Spitznagel’s worry that he has developed genuine affection for Beck, whom he referred to a cardio surgeon for his bypass surgery some four years ago. “Gene is a tough guy, aren’t you?” he says. “He’s a survivor.”

Beck is a man of few words. “I got no complaints,” he says. “Just gotta live to be a hundred.”